Edit: I was succesful in my application, and as of June 2017 am now a Principal Fellow of the Higher Education Academy!

—–

I just finished writing a new application to the Higher Education Academy. I became a Senior HEA Fellow in mid-2015, and posted about my teaching philosophy then. This time, I’m going for the big one: Principal Fellow. There are about 700 Principal Fellows worldwide, and these people tend to be highly experienced senior staff with strategic institutional and sectoral leadership roles in learning and teaching.

I’m applying for my Principal HEA Fellowship through QUT’s scheme QALT (QUT Academy of Learning and Teaching). My application involved about 8,000 words, all-told : a reflective account of practice demonstrating that I meet all Dimensions of the PSF at Descriptor 4 level, a record of educational impact (list of roles and activities), three advocates reports, and my learning and teaching philosophy statement.

This application drove me nuts. It was much harder to do than my previous one, and not just because it was four times the length. I had trouble pulling apart my integrated experiences to address the different criteria. I dithered over my reflections and wondered exactly which examples of practice should go where. It took me a total of two months at 1-2 hours each work day to draft and then edit the thing.

I reached the teaching philosophy part and thought I’d be fine. ‘Excellent’, I thought. ‘I can cut corners here by using my philosophy from my SFHEA application!’

Except no.

I copied-and-pasted my teaching philosophy statement, read it over, and realised it didn’t fit. Not because my philosophy of teaching has changed; but because the focus and scale of Principal Fellow is completely different. In my SF application, I spoke largely about the learner, and the role of the teacher and the learning environment. In my PF application, I started my philosophy the same way, but got far more into what I believe higher education is for, and which pedagogic principles and practices should infuse everything we do. It got quite grandiose, really.

Anyway, here it is. Upon reflection, most of my work has this kind of focus rather than at the SF level, so while the PF application was harder to write, the PF aligns better with my thinking and practice. Cross fingers that I am approved — my application now goes to three reviewers, and I will hear back in about 8 weeks.

——

I believe that higher education is vitally important to personal, social and economic well-being and growth in the 21st century knowledge society. Universities are responsible for teaching high level capabilities that are needed for leadership, social responsibility, innovation and problem solving, all of which are integral to navigating a successful global future. Given this mandate, I feel that contemporary university programs must be orientated towards real world relevance and application – that is, they must be of use – as well as continuing to support learners to develop disciplinary depth and high level critical capabilities grounded in history, theory and context. Education for relevance and application should include the development of ‘future capabilities’, including disciplinary agility, enterprise and entrepreneurship, digital literacies, social network capability, and career/learning self-management, all of which are often sorely lacking in university graduate capability lists and curricula (Bridgstock, 2009; 2015). I often argue that in a world where more and more information is available online for free, provision of pre-digested curriculum content is much less important than previously. Universities will soon be differentiated by the provision of quality learning experiences that develop future capabilities, and the extent to which they foster the growth of learners’ professional relationships and networks.

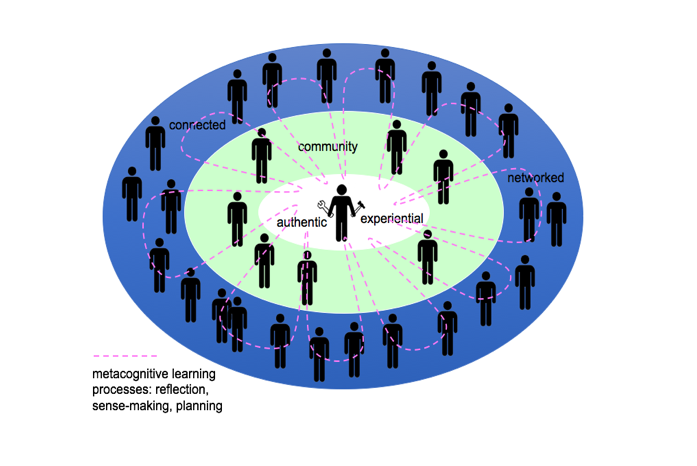

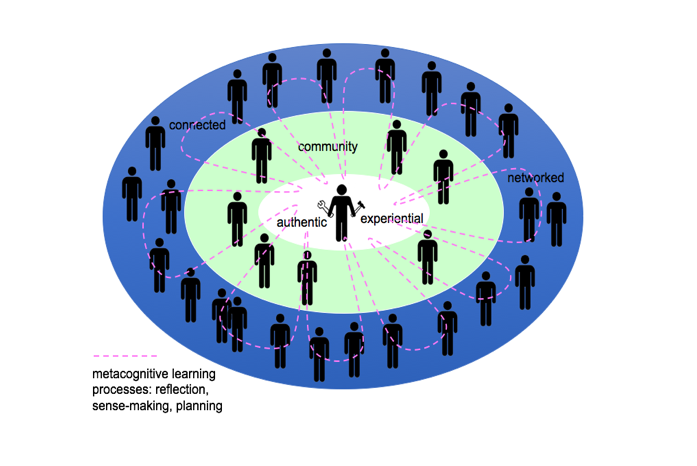

Thus, in order to meet the future capability needs of learners, teachers and educational institutions need to be future capable as well. My perspective on the dominant pedagogic approaches taken by the future capable is exemplified in my distributed knowledge network model of the university depicted in the figure below (Bridgstock, 2016). The model is based on research I conducted into the actual and preferred learning strategies of digital industry professionals (Bridgstock, 2016, published online), and is designed to create a responsive, continually updating curriculum. It has grounding in, and integrates ideas from, experiential, active learning theories and authentic learning (Dewey, 1938; Herrington & Herrington, 2005), social constructivism (Berger & Luckmann, 1966), communities of practice and enquiry (Lave & Wenger, 1991) and connectivism (Siemens, 2005).

At the centre of the model is the learner who is engaged individually or in a group in task- or enquiry- based experiential learning. The green ring depicts their learning community, which may include other learners at different levels of capability, teachers, and industry/community members. The community is embedded into a much larger distributed knowledge network comprising global digital and face-to-face connections – such as learners, teachers, practitioners, industry, users, and other interested individuals. The acquisition of capability occurs in cyclical manner between authentic activity and the ‘classroom’ (whether physical or virtual), with teachers scaffolding learners’ processes of reflective metacognitive learning how to learn and emergent meaning making (Nonaka & Toyama, 2003). In strong contrast to the traditional ‘sage on the stage’ transmissive model of education on the 20th century (King, 1993), 21st century academic teachers must guide, coach, and mentor. They support learners to plan their learning, and then to filter, compare, contrast, and re-contextualise learning strategies and experiences, and identify new sources for relevant knowledge and skill acquisition, which is what learners will then do for themselves continually throughout the rest of their professional and personal lives. The learner is co-designer and co-constructor of their learning, which may traverse formal, informal, curricular and co-curricular realms as needed.

In the future capable university, teachers are vital to ‘bottom up’ educational innovation and growth, and to the ongoing facilitation of high quality learning experiences (Salmon & Wright, 2014). For teachers to be effective, they must be supported by organisational structures and processes that are germane to new ways of working and teaching. Teachers’ bottom up actions must also be met by complementary ‘top-down’ policies and strategies. Thus, I work with teachers and institutional leaders to build future teaching capability. I believe in the power of transformational leadership in stimulating organisational change (Avolio, Zhu, Koh, & Bhatia, 2004) that inspires and stimulates new ways of thinking, and affirms and capitalises on existing practice.

Avolio, B. J., Zhu, W., Koh, W., & Bhatia, P. (2004). Transformational leadership and organizational commitment: Mediating role of psychological empowerment and moderating role of structural distance. Journal of organizational behavior, 25(8), 951-968.

Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. London: Penguin UK.

Bridgstock, R. (2016). The university and the knowledge network: A new educational model for 21st century learning and employability. In M. Tomlinson (Ed.), Graduate Employability in Context: Research, Theory and Debate. London: Palgrave-MacMillan.

Bridgstock, R. (2016, published online). Educating for digital futures: What the learning strategies of digital media professionals can teach higher education. Innovations in Education and Teaching International.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education: Simon and Schuster.

Herrington, A., & Herrington, J. (2006). What is an authentic learning environment? In A. Herrington & J. Herrington (Eds.), Authentic learning environments in higher education (pp. 1-13). Hershey: Information Science Publishing.

King, A. (1993). From sage on the stage to guide on the side. College Teaching, 41(1), 30-35.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity: Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 2(1).